(This is from 2008, reposted now with some light updating).

Like a lot of people, I’ve turned to music for solace, not just right now, but through my past. One particular post-juvenile heartbreak was accompanied by Frank Sinatra Sings for Only The Lonely and In a Silent Way on endless repeat. And Jack Daniels on endless repeat as well.

But we age, and hopefully we mature: our hide thickens – but not too much – we tolerate more, but also have a better idea of what matters to us, and eschew nonsense, and our tastes deepen. We may even find ourselves more interested in questions that answers. If so, then our need for solace comes from, unfortunately, more profound and difficult events, and the music in which we find that solace changes. Pop music still has its niche, especially in remembered experience, moments from the past that can exactly recall something needed or welcome in the now. But classical music draws us more firmly and insistently and offers the depth and complexity that can properly mirror what troubles us. And in the solace of “classical” music, we find a divide between the Classic and the Romantic, and how they touch our hearts and minds.

What is it, exactly, that troubles us? Beyond the actual event of tragedy, it is the disorder in the heart and mind – a bit of disorder is a necessary part of life, but when it crowds out everything else, it becomes a small bit of madness we must fight against so we may get out of bed, and think, and feel, and eat, and walk and laugh. I think H.P. Lovecraft expresses both sides of this best in the beginning of “The Call of Cthulhu:”

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

It is music that can counter this despairing view, fascinating and sympathetic as it may be. Music that works is based on some idea of order, even if the immediate sensation can be chaotic. Throwing the I Ching to generate musical decisions is random only within the structured limits of that system – the same method produced a structured, readable novel. Musical thinking, manifested in a series of sounds, is an imposition of order onto the randomness of everyday existence, it is a way to piece together dissociated knowledge without driving one to madness, and it can be a lifeline away from the forces of madness, and maddening sorrow.

Haydn and Mozart are two of the paragons of this sense of order. Taken in the abstract, the ideal of the Classical style which they pioneered is one where order entirely takes the place of content. That is, the the structure of each musical moment and gesture through time is the content itself, and that content takes the form of a long, but not necessarily straight, line that proceeds from point A to ultimately either point B or a return to A. Of course, Haydn and Mozart were thinking, feeling men with a sense of beauty and satisfaction, so their works are frequently both ravishing and moving. I find Haydn’s symphonies H.I 26 and 49, known as “Lamentations” and “La passione” respectively, particularly powerful this way, with their alternating periods of intensity, stress and repose yoked into a structure that is satisfying and comforting in its orderliness. He offers a balance, an acceptance that we can proceed through the day while carrying a burden of sorrow, that we can because often we must.

Mozart offers a sympathetic type of comfort, that we can find our way to clear thinking and serenity despite the worst circumstances. I think the greatest expression of this, and in fact the works in musical history that express this better than any others, are his piano concertos. The concerto form has a built-in struggle between the adversarial opposition of the soloist and orchestra. Even though, as with much of Mozart, the piece is composed with a sense of mutual support, it is still the soloist who must shine above the ensemble. Mozart succeeds at this through writing of absolute clarity, brilliance and deep and gentle sensitivity. He opens with the orchestra stating the theme, the soloist repeating it back, and then sonata form opens the door to an internal rumination on the theme by the soloist, a musical passage which is invariably thoughtful and just as clear and lyrical in its expression. Mozart explores the internal landscape, the sense of how one feels in that moment, with introspection necessary to gauge the problem, the sense of one’s sorrow. And Mozart is one of the most humane of all composers, so the path he offers us is warm and gentle without being sentimental.

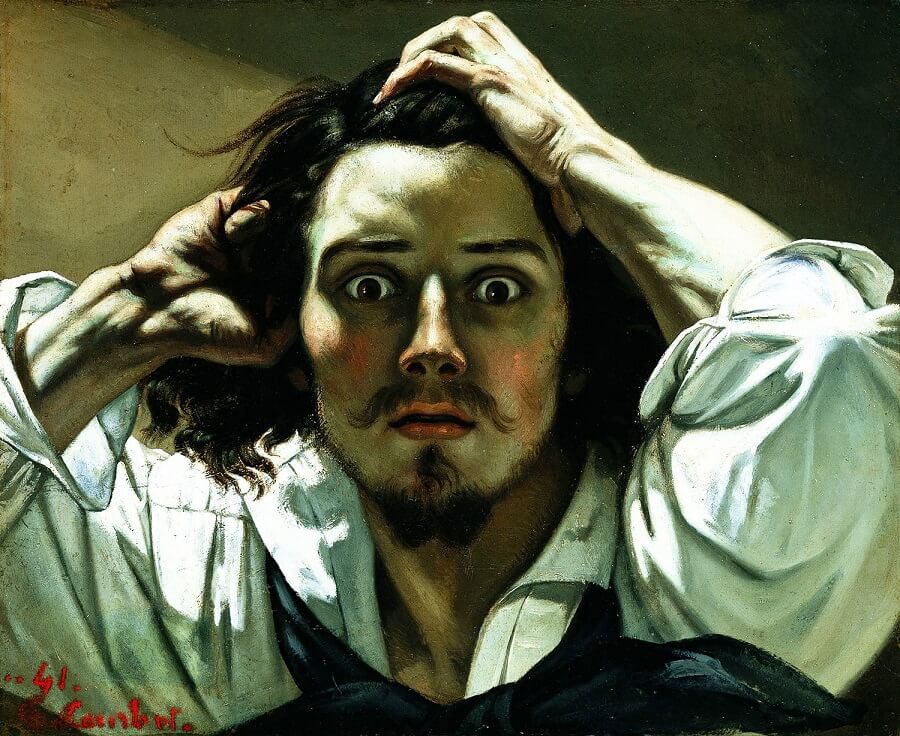

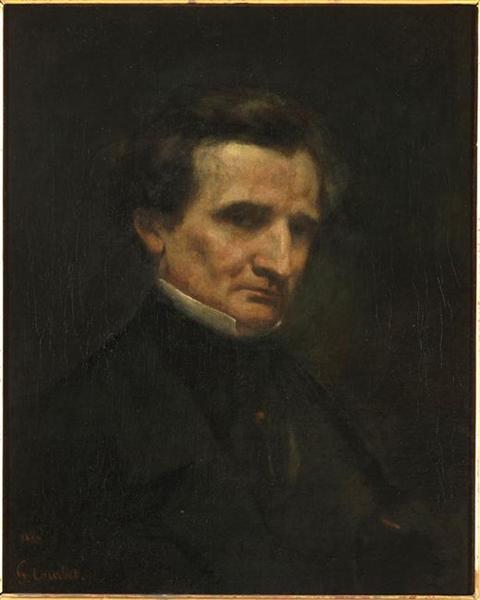

In sorrow, we are filled with sentiment, and sensation, to which the sentimental offers false comfort. But sympathy for and with the sentiment is a solace, and the Romantics give us that. When we listen to Beethoven, Schumann and Brahms we are hearing different aspects of a shared experience, that of merely living. If Classical music is the data of a human census, Romantic music is the anecdotes, the telling of how things were for him and her. It is the great genius of these composers that they can give us the joy and shit of life in personal measures with the skill so that it all sounds clearly in our ears and makes sense in our minds. How they each react to the good and bad fortune of life is different, and complimentary. Beethoven cries out in anguish, unafraid to press on the wound to produce the deepest hurt, and then finds new energy in his despair and storms his way, through will and faith to the heavens. Schumann, in those times when he found his way to sanity, expresses a joy and wonder about being alive and the world around him, each period of mania a new birth, yet with an underlying unease that something is terribly wrong.

And then there is Brahms. It’s no surprise that the New York Philharmonic programmed his German Requiem in response to 9/11, it is music about and for those seeking comfort in a time of grief, and Brahms is the most comforting of composers. His genius is more a public one than that of Beethoven or Schumann, he doesn’t set his expression apart as something for us to regard, as something human yet as unique and special as those two men themselves. Brahms is the everyman, engaging us diffidently and ruefully in conversation at the bar, telling us he knows exactly how we feel, because he’s been there too, and imparting a quiet and implicit confidence that things will be better again, that this moment will not pass so much as become a part of the long skein in life, and make that life more lived and understood, more appreciated. Listening to Brahms when we are in sorrow is like reading great poetry in the same state; the poetry does not replace the sorrow with happiness, but the sympathetic voice of the poet makes us feel we are not alone, that we are understood, that others have been in sorrow and returned whole people, with an even greater understanding of happiness and hope.

“A reputable music blog.”

“He gets it! He knows music!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.